Instructions!

To open the media file (video,image etc) please click the icon, to see the synopsis & artist’s bio please click the cover poster

Carla Della Beffa (Italy)

Firewall, 2022, image

Carla Della Beffalives and works in Milano and in Paris and

has had an art website since 1996. International curators have been selecting some of her netart works for their reviews since 1997. Many of her works are made expressly for the net, and then sometimes develop into exhibitions, installations, interdisciplinary projects. She makes monothematic series of digital photos and just published a book about one of them, BabelFood.

Della Beffa started making videos in 2000: the first one, “Three liters approx.â€, was shown at the Modern Art Gallery in Turin. The three following were chosen by curator Manuela Corti for the Polyphonix festival, Paris, Centre Pompidou, 2002.

She has just finished her fifteenth video, and is showing some of them in international reviews around Europe.

Â

Â

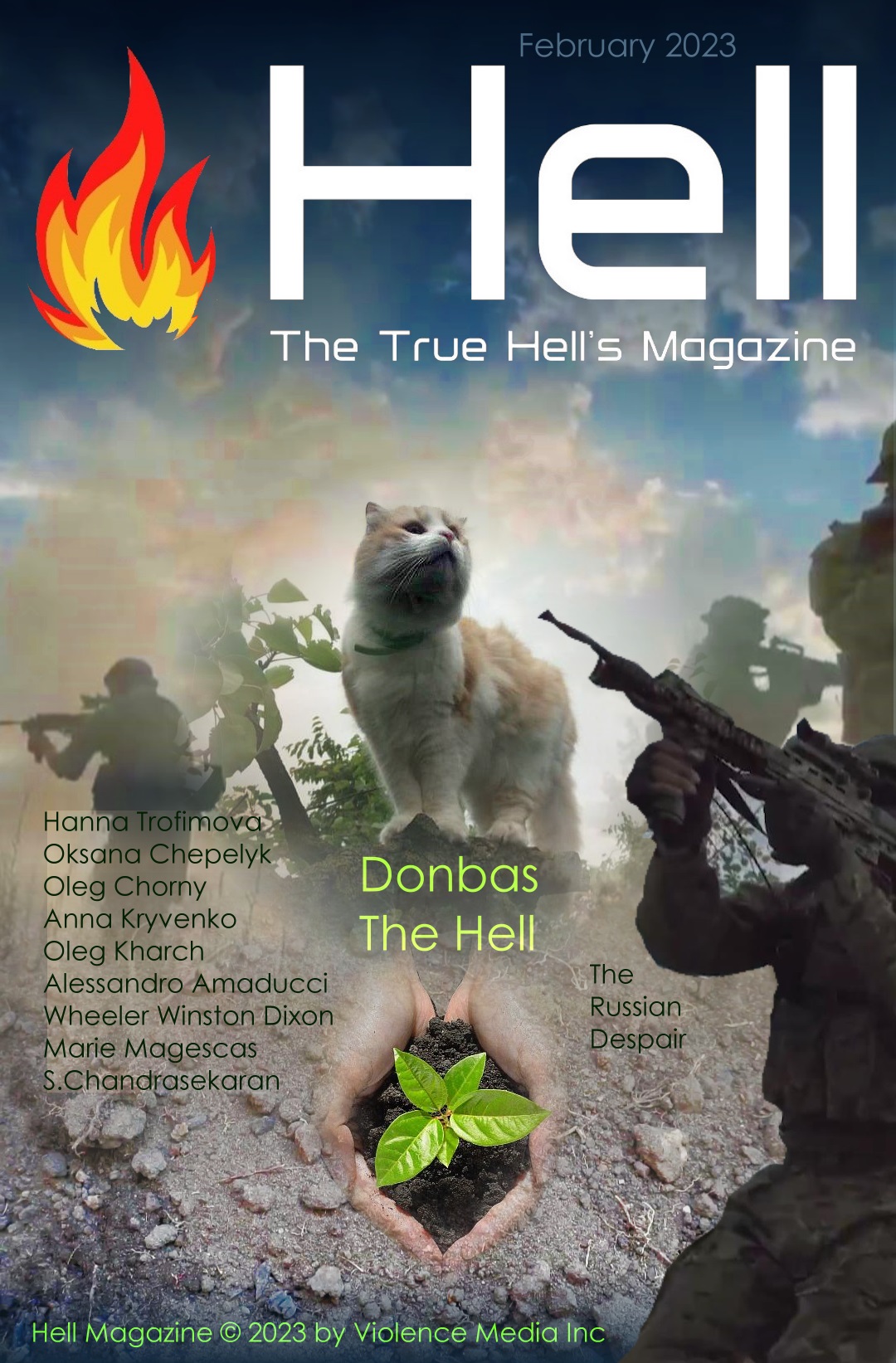

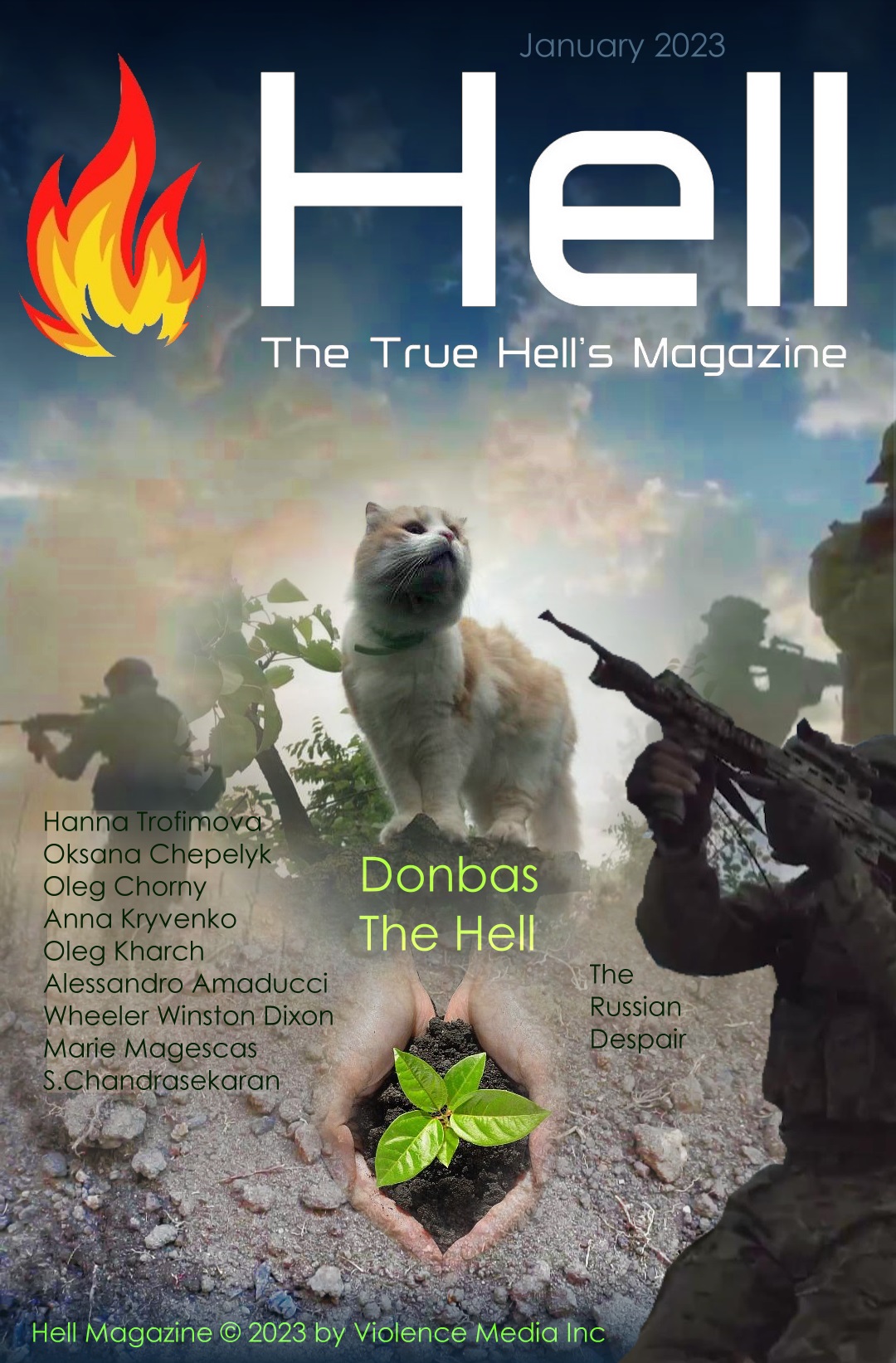

Donbass - the Hell 60 Minutes - Fighting for one's Territory

Donbass - the Hell 60 Minutes - Fighting for one's Territory

DONBAS – The Hell

60 Minutes on Fight on Donbass

Hanna Trofimova (Ukraine) , Ash. 2022, 2:28

Oksana Chepelyk (Ukraine) – Premonition of War, 2014, 6:65

Oleg Chorny (Ukraine) – Summer 2014, 2014, 7:25

Anna Kryvenko (Ukraine) – Silently Like a Comet, 2014, 8:14

Oleg Kharch Group (Ukraine) – Putin’s huylo session at a parade of 30 years, 2021, 2:08

Alessandro Amaducci (Italy) – Not with a Bang, 2008, 04:30

Wheeler Winston Dixon (USA) – PERPETUAL WAR FOR PERPETUAL PEACE, 2022, 5:00

Marie Magescas (France) – WARdesease, 2010, 8:30

S.Chandrasekaran (Singapore) – Marking for Ukraine/STOP THE WAR, 2022, 10:00

The Donbass Nightmare

by Hiroaki Kuromiya

The past has shown that Donbass as a region has not been truly loyal to any government. That could still be fatal for Moscow.

Members of a separatist combat unit in Donetsk.

The current war in Donbass is difficult to understand at first glance. Almost all Western reports describe it as a battle between the Ukrainian military (and pro-independence volunteers) and pro-Russian separatists (directly, albeit covertly, supported by the Russian government). There is some truth to this account. Despite Moscow’s denials, this is also Russia’s war against Ukraine: the Russian military is directly intervening in the conflict on behalf of the separatists. However, it is completely unclear whether the pro-Russian fighting spirit in the Donbass is as deeply rooted as is reported. Without Russia’s direct support, the separatists in Donbass would likely quickly suffer defeat at the hands of Ukrainian forces. What is certain is that Donbass as a region has never been truly loyal to any government or ideology. This will prove to be a real problem for both Kyiv and Moscow, no matter how the conflict ends.

For a long time, many politicians feared the political fighting spirit of this Ukrainian-Russian border region. The soot-blackened faces of Donbass workers have long symbolized the recalcitrance of politics in the region. Between 1917 and 1921, during the years of revolutionary uprising and civil war that followed, Donbass passed through many hands. However, none of the parties and governments involved (communists, anti-communist whites, various Ukrainian nationalists) ever gained a foothold there. When the communists in eastern Ukraine seceded their country and the surrounding industrial regions from Ukraine in 1918 and declared the Donetsk-Krivoi Roh Soviet Republic because they opposed the new independent Ukrainian government, the communist leader Vladimir Lenin was against it. He saw the republic as weakening Ukraine by depriving it of its “proletarian base”. With this, Lenin recognized the Donbass as part of Ukraine. Lenin’s judgment is understandable: however Russified Donbass may be culturally and linguistically, ethnic Russians have never been in the majority here, either before or since. The Donbass was and is predominantly Ukrainian.

Throughout the communist era, the Donbass, a vast industrial center of mining and metallurgy, remained Moscow’s problem child. Because workers were constantly needed here who were willing to take on hard and dangerous jobs, it remained the magnet for fugitives and fugitives that it had been before the revolution. Those who had reason to flee (from political persecution or economic hardship, for example) fled here and found refuge underground, both literally and figuratively. Donbass was a land of refuge and freedom. After World War II, Ukrainian partisans who failed to escape to the West were advised to go and hide in Donbass. At the time of the anti-cosmopolitan campaigns in Stalin’s last years, the Donbass attracted Jews, who realized that conditions here were more liberal than elsewhere. One of them was the father of Israeli politician Natan Sharansky: when anti-Semitism in Odessa prevented him from working there, he was told to “try his luck in Stalino [now Donetsk]”. Like Siberia, Donbass was also a penal colony. The extremely harsh and grueling working conditions in industrial regions made them convenient dumping grounds for politically undesirable individuals and groups. Thus, like the gulags, the Donbass became a place where forbidden political ideas spread widely.

Donbass was also a place of democratization. During the German occupation of World War II, Ukrainian nationalists sympathetic to the fascist ideas of Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco moved from the western regions to the east, Donbass, to win the minds and hearts of its people. However, the local population rejected them, and some of the fascist nationalists even ended up supporting a democratic Ukraine. Later, in the Brezhnev era and even before the Solidarnosc movement in Poland, Donbass became a major center of the independent (non-Soviet) trade union movement. Some important Soviet freedom fighters also come from the Donbass. One of them is the Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus. He died in a Russian labor camp in 1985. (The memorial plaque put up for him at Donetsk National University in 2001 was recently removed by anti-Ukrainian forces.) Believing that they would be better off without Moscow, an overwhelming majority of the Donbass population (over 83 percent) supported Ukraine’s independence in 1991 . This independent Ukraine was more of a disappointment than a satisfaction. Hence the widespread anger in Donbass.

This does not necessarily mean that the Donbass population is pro-Russian. While many see Russia as more promising than Ukraine today, they may think differently tomorrow. Despite shrill political rhetoric to the contrary, ethnic and language-political Russian-Ukrainian issues have not played a major role in Donbass politics, neither in the past nor today. In many ways, the people of Donbass behave like the ancient Ukrainian Cossacks who founded the “wild field” in the border region of Moscow, Poland and the Ottoman Empire in the 15th and 16th centuries, where they wanted to find freedom and happiness. Depending on the changing political situation, they joined forces with each of these powers to ensure their existence and well-being. Thus their at-time pragmatic alliance with the Moscow tsar against Poland in the mid-17th century ended with the Donbass and surrounding regions falling to Moscow. In the rough world of the Cossacks, democratic and egalitarian principles were by no means unknown; rather, they were the founding ideals of the modern, independent Ukrainian state, which distinguished it from “autocratic Russia” and “aristocratic Poland”. In this sense, despite its supposedly “pro-Russian” orientation, the Donbass appears to be deeply Ukrainian.

As independent Ukraine became free, or at least freer than in the Soviet period, Donbass no longer needed to be the place of freedom and was now just one, albeit unruly, region of a new country. Unlike the western and central regions of Ukraine, however, the Donbass is a highly developed industrial center that generates significant national wealth. It is no coincidence that many of the rich Ukrainian men (among them the richest man in Ukraine, Rinat Akhmetov) come from Donbass.

The Donbass, citizens as well as oligarchs, adjusted to the new political reality of the post-Soviet era. Despite occasional separatist calls, Donbas saw its future overall within an independent Ukraine, while not rejecting ties with Russia for good reasons (everyone wants good neighborly relations!). Then, however, the Donbass as a whole changed its political strategy. After Ukrainian independence, he began to behave quite atypically: he tried to take over the Kiev central power. This can be called the Yanukovych phenomenon.

Viktor Yanukovych almost managed to steal power in 2004. In 2010, he succeeded in winning the presidency through elections, which the Orange Revolution of 2004/05 had prevented. As long as the Donbass population believed that their interests and voices were reflected in national politics, they seemed content with the Yanukovych phenomenon and showed little interest in separatism. Even when Yanukovych was expelled by the Euromaidan movement in February 2014, the Donbass population did not seriously consider separatism. He was nothing more than an unrealistic possibility. In a strange way, the Yanukovych phenomenon even indicated the beginning, albeit massively influenced by Russia, of Donbass integration into the Ukrainian body politic. It was Russia’s military intervention that completely changed the political scene.

The Russian War Responsibility

In March-April 2014, Moscow imposed military force on Donbass to control it, under false accusations that ethnic Russians and Russian-speaking populations were being persecuted, although Moscow to this day denies the presence of Russian Federation military forces. A month earlier, Moscow had already taken Crimea with military force and under the guise of local volunteer forces.

President Vladimir Putin’s interventions may seem like spontaneous decisions. But in light of Russian and past Soviet military interventions, these recent cases were certainly planned, at least as a possible scenario of creating a larger Russian sphere of influence or expanding Russia’s imperial reach. Putin’s use of the old historical concept of “New Russia” to justify his military intervention is no accident. There is reason to suspect that at least two forms of internal subversion have been in use for some time. One of them is the practice of offering Russian passports to residents of border regions, including Donbass. This form of subversion has long been used by Russian and Soviet governments for covert territorial expansion. When necessary, Russia continues to invoke the protection of its citizens to justify military intervention. The second form of covert subversion is the deployment abroad of covert “influencing agents” who may be termed political “sleeper cells.” Russia and the Soviet Union have traditionally been extremely adept in this area. Ukraine is a young and still unstable country with an unpredictable future. With Ukraine’s borders practically open, it would be relatively easy for Russia to recruit people to work in the interests of Moscow, the former capital of the Soviet Union. Nostalgia and the desire for stability are another important factor, after all, the majority of the Ukrainian population was born under Soviet rule. Also important are threats, blackmail and other unspeakable methods that this business has in store around the world.

President Putin justifies his camouflaged and veiled war with Russia’s national security concerns. But like Russia, Ukraine has a right to national security. Russia violated Ukraine’s law by unilaterally invoking its own. This is not new either. Russia still accuses Poland of causing World War II by not giving in to Moscow’s demands. Moscow studiously forgets that it was Moscow and Berlin that started World War II by conspiring to destroy Poland. Russia is certainly behind the current war in Donbass.

Moscow’s reference to security concerns is more rhetorical than substantive. Of course, national security is a serious matter. Russia’s concern about the expansion of the western world to its borders is also understandable. Both sides are responsible for the distrust between the West and Russia. While the West’s self-centered behavior on the international stage has contributed to Russia’s alienation from the West, Russia’s self-centered behavior has created at least as much alienation not only from the West, but also from Russia’s former Moscow-controlled satellite states.

Moscow has its own problems in every respect, which the West, for its part, has largely solved. For example, President Putin still thinks Moscow has the right to intervene to “protect” the Russian-speaking population on the Eurasian continent, in other words, to occupy and annex countries like Crimea and Donbass. This imperialist claim is highly anachronistic. Does England have the right to intervene in New England and the US? Does Mexico have the right to intervene in the states of New Mexico, Texas, Arizona or California in the United States? British scientist Timothy Garton Ash reports that in 1994 he was dozing off while attending a round table in St. Petersburg, Russia, when a “little squat man with a rat-like face” suddenly woke him. “Russia,” he said, “voluntarily ceded ‘huge territories’ to former Soviet republics, including areas ‘that historically have always belonged to Russia’,” presumably Crimea, eastern Ukraine, northern Kazakhstan, and the like. According to this man, “Russia could not simply abandon ’25 million Russians’ now living abroad to their fate. The world must respect the interests of the Russian state ‘and the Russian people as a great nation’.” This man’s name was Vladimir Putin.

Do the Russian people think the same way? If you believe the polls (which you can’t necessarily do given the government’s control over the mass media), the majority do. That, too, seems anachronistic. Would the German people be pleased if Germany regained the Sudetenland or Kaliningrad (formerly Koenigsberg)? Almost certainly the German population as a whole would not be pleased. Would the Polish people be happy if Warsaw conquered eastern Galicia through covert military action? Most likely not. Over the course of the twentieth century, with its two world wars, Western countries have outgrown their imperial stupidities. Russia obviously isn’t. Both the Russian government and the Russian people must seriously consider this problem.

Final remarksNobody knows in which direction Donbass will develop. Like many similar geopolitical issues, the Donbass issue may be “solved” through the policies of the great powers and without much regard for Ukraine or Donbass. In any case, it was Moscow’s military intervention that created the Donbass nightmare. Many people in Donbass say that the whole military conflict is incomprehensible and downright absurd. There’s a reason for that: it was designed in secret and cleverly camouflaged by outsiders.

It is true that Donbass has long been a place of resistance to metropolitan power centers, always resisting outside authority. The motto of Donbass (from a poem by the WWII-era local miner Pavel Besposhchadnyi) is:

No one brought Donbass to its knees! Nobody will make it! [Donbass nikto ne stawil na koleni / I nikomu postawit ne dano!]

In 1991 and thereafter, however, the Donbass began to locate its future in an independent and free Ukraine because it saw no alternative. Moscow violently reversed this turbulent development. Ultimately, by abolishing the Ukraine-Russia border in the Donbass region, Moscow revived the legendary unruly Wild Field. Small sections of the Donbass population began to take up arms against Kyiv, supported by camouflaged Russian soldiers and secret agents.

Russian poet Nikolai Domovitov, who lived in Donbass in the 1950s and 1960s, wrote about Donbass:

Neither Ukraine nor Rus, [Ne Ukraina i ne Rus] I fear you, Donbass, I fear you. [boyuz, Donbass, tebya boyuz.]

Domovitov’s fear proved prescient. Did Moscow really want to occupy this dreaded region when it invaded eastern Ukraine? Does it still want that? Moscow has unleashed the fearsome spirit of the Donbass and may regret it because the Donbass separatists will not accept Moscow’s autocratic rule tomorrow, whatever their rhetoric today. Even Akhmetov seems to be covering himself by not publicly supporting Kyiv or the separatists. The Donbass population as a whole will not accept Moscow’s rule. This will benefit Kyiv. But can Kyiv win the minds and hearts of the Donbass population? Moscow can withdraw and end the war if it wants to. The rest of the rest then falls on Kiev’s shoulders.

Hiroaki Kuromiya, Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. New York, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Â

Auschwitz - The Hell 60 Minutes on 27 January 2023

Auschwitz - The Hell 60 Minutes on 27 January 2023

Auschwitz – The Hell

78 years after the Liberation of Auschwitz

Isabelle Rozenbaum (France) – Two Trees, 2009, 11:47

Heike Liss & Thea Farhadian (USA) – ZeroPointTwo, 2007, 18:00

Roland Quelven (France) – Death Fugue B50.02 – L19.20, 2013, 3:15

Todd Herman (USA) – I Cannot Speak Without Shaking, 2007, 5:00

Hagit Kastel Nachsholi (Israel) -Hollacost, 2022, 1:47

Maria Korporal (NL) Anne Frank, 2014 , 6:20

Dova Cahan III (Israel) – My Visit at Ferramonti of Tarsia, 2016, 12:10

Elie Wiesel Auschwitz Speech

After Auschwitz

This is a speech delivered by Elie Wiesel in 1995, at the ceremony to mark the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

“After Auschwitz, the human condition is not the same, nothing will be the sameâ€

Here heaven and earth are on fire.

I speak to you as a man, who 50 years and nine days ago had no name, no hope, no future and was known only by his number, A70713.

I speak as a Jew who has seen what humanity has done to itself by trying to exterminate an entire people and inflict suffering and humiliation and death on so many others.

In this place of darkness and malediction we can but stand in awe and remember its stateless, faceless and nameless victims. Close your eyes and look: endless nocturnal processions are converging here, and here it is always night. Here heaven and earth are on fire.

Close your eyes and listen. Listen to the silent screams of terrified mothers, the prayers of anguished old men and women. Listen to the tears of children, Jewish children, a beautiful little girl among them, with golden hair, whose vulnerable tenderness has never left me. Look and listen as they quietly walk towards dark flames so gigantic that the planet itself seemed in danger.

All these men and women and children came from everywhere, a gathering of exiles drawn by death.

In this kingdom of darkness there were many people. People who came from all the occupied lands of Europe. And then there were the Gypsies and the Poles and the Czechs … It is true that not all the victims were Jews. But all the Jews were victims.

Now, as then, we ask the question of all questions: what was the meaning of what was so routinely going on in this kingdom of eternal night. What kind of demented mind could have invented this system?

And it worked. The killers killed, the victims died and the world was the world and everything else was going on, life as usual. In the towns nearby, what happened? In the lands nearby, what happened? Life was going on where God’s creation was condemned to blasphemy by their killers and their accomplices.

Turning point or watershed, Birkenau produced a mutation on a cosmic scale, affecting man’s dreams and endeavours. After Auschwitz, the human condition is no longer the same. After Auschwitz, nothing will ever be the same.

As we remember the solitude and the pain of its victims, let us declare this day marks our commitment to commemorate their death, not to celebrate our own victory over death.

As we reflect upon the past, we must address ourselves to the present and the future. In the name of all that is sacred in memory, let us stop the bloodshed in Bosnia, Rwanda and Chechnia; the vicious and ruthless terror attacks against Jews in the Holy Land. Let us reject and oppose more effectively religious fanaticism and racial hate.

Where else can we say to the world “Remember the morality of the human condition,†if not here?

For the sake of our children, we must remember Birkenau, so that it does not become their future.

Â

Peace Letters Winter Marathon 2023 Back to Hell

Peace Letters Winter Marathon 2023 Back to Hell

Peace Letters Winter Marathon 2023 – Back to Hell

60 Minutes on Fight on Donbass

Peace Letters to Ukraine 14

Today, 5 March 2023 the long Peace Letters marathon course, starting on 12 December 2022 coming to an end on an historical date – the war criminal Vladimir Putin annexed after 2014 the Crimea, the next parts of the Ukraine illegally.

But that’s the next fundamental mistake by the Russian emperor in mental agony. Today the Ukraine – tomorrow the rest of the world! That’s conceptual brain cancer!

I would like to thank all the artists and other cultural instances accompanying my artistic/curatorial activities since 2000, because a big share of them are/were involved in the Peace Letters Project – a selection of more than 200 venues was co-hosting and more than 500 artists from all continents were running a marathon course which had been in fact only partially virtual, because its aims, the solidarity and fighting for Peace and Freedom are/were true, real and physical. Also, the venues, the artists and artworks were true, real and physical – it would be completely wrong to misestimate the Peace Letters project as one of the countless leisure activities online.

My person was dedicating 80 days exclusively to Ukraine taking high risks in many ways, for instance the permanent attacks by Russian hackers on my server or the unusually long-lasting heatwave causing my complete circulatory collapse/breakdown. Anybody else would have stopped /given up, but I continued, because I never give up.

The annihilation war against Ukraine has its counterpart in Cologne, threatening continuously my physical existence. While the Russian aggressor is well-known to world, the enemy in Cologne has many faces of corruption. But differently than in Ukraine, in Cologne a constitutional court will stop this war at latest in 2023.

Cutting my solidarity for Ukraine, would have meant to give up in my own case. Therefore, The Peace Letters project will be continued after the marathon arrival in Ukraine today – simultaneously in Lviv – Kiev and Kharkiv- these three venues of my activities, however, are standing for all places in Ukraine, thus whole Ukraine and its inhabitants, this is particularly good for the illegally annexed areas.

After some recovering from the rigors of the marathon – The Peace Letters Project will be continued as a corporate part of The Violence Project – but more relaxed, under less stress than before, because preparing during the marathon for each day new screening programs valid only for one/later two days was not only an unusual curatorial, but labour intensive task, it required a lot of motivation while at the same time declining solidarity!

The 13th part – sending the message of the positive creativity – via the specific solidarity screening program action of “Peace Letters Marathon” @ Alphabet Art Centre – starting on 7 July 2022 the exactly 90 days lasting Marathon screenings. The daily changing programs include all videos and artists participating in “Peace Letters 01 – 10”.

Cultural and artistic networking is representing one way how art can serve as a tool to show and confirm solidarity with the Ukrainian people – for Peace and Freedom – not just on times of war, the Russian-Ukraine War. But it’s freedom, of course, as it is understood in a liberal democracy, as it is possible only through the diversity as a result of networking.

Venues

VisArts Center Rockville (MD/USA) – 07-08 May 2022

Thessaloniki Municipal Art Gallery (Greece) 18-20 May 2022

Torrance Art Museum Los Angeles (CA/USA) – 04-25 June 2022

Rhizome DC Washington DC (USA) – 07 July 2022

IzDoc Izmir (Turkey) – 20-22 January 2023

ENTER – Peace Letter Winter Marathon80th day – Back to Hell in Ukraine

Â

Hanna Trofimova is a Ukrainian director and artist – September 1, 1986 was born in Vinnytsia, Ukraine

Education

2003 -2008 – The Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Kary Theatre, Cinema and Television University, TV director 2007-2021 – worked as a director on television

Participation in exhibitions:

12.04 – 14.04.2019 – showing video art “Again” in the art program of the European Lesbian Conferences (Kyiv)

09.10 – 11.10.2020 – ARTLAB exhibition with the support of the NGO “KyivPrideâ€, video installation “Come in†(Kyiv, IZONE)

May 2022 – Installation “Parts”, was realized within the residence of Ukrainian artists Villa Mueller, Feldkirch (Austria)

May 2022 – video installation “Extent”, was realized within the residence of Ukrainian artists Villa Mueller, Feldkirch (Austria)

Festival:

2022 – documentary film “When will the winter of 2022 end?”, DOK Leipzig (Germany) – International Competition Short Film